| Q. I notice that in your book The Beauty Behind the Mask you reference The Modern Reader’s Bible, edited by Richard Moulton, and you offer some criticism of his choice of book order and book titles. I own a copy of that book, as well as Moulton’s book The Literary Study of the Bible, both of which I purchased years ago at a used book store. He has other books about the Bible and literature that can now be found online. Moulton aimed to lay out the text of the Bible according to the literary structure—perhaps a forerunner of The Books of the Bible edition. Although I do not regularly read from The Modern Reader’s Bible, I do refer to it to notice how it lays out the poetic structure, and I notice that Moulton in his notes has an overarching system of the literary forms of the Bible, from simple to complex. My question is how valid and useful are his views, his literary theory of the Bible, and his Bible edition, all more than 100 years old, considered today? Did he have insight that is still valuable and been forgotten, or has modern scholarship rendered it obsolete? The short answer to your question is that Moulton’s analysis, in my opinion, is still very valuable. While, as you noted, I differ with him about some details, overall he is asking the same questions and pursuing the same goals as we did in producing The Books of the Bible. Now here is the long answer to your question. God gave us his word in the Bible by using not only existing human languages—Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek—but also by using existing human literary forms: psalms (songs), epistles (letters), parables, proverbs, stories, visions (dreams), and so forth. If we really want to understand what God is saying to us through the Bible, we need to appreciate the Bible for what it is: a collection of literary compositions. That is what the Bible is made of. Unfortunately, most people who engage the Bible treat it as if it were made of something else. One common way to engage the Bible is as if it were made up of “verses.” These are taken to be short doctrinal propositions or “precious promises” or “thoughts to live by.” Since Bible verses each seem to have their own indexing (e.g. John 3:16), and since published versions of the Bible number them right in the text (some editions even print each verse as a separate paragraph), they seem to be intentional divisions of the text—the basic building blocks of the Bible. But as I point out in The Beauty Behind the Mask, chapters were only added to the Bible around the year 1200 and verses were only added around 1550. They are late, artificial divisions introduced for convenience of reference, most often for the sake of reference in the course of discussions and debates. It is not a coincidence that verses were added to the Bible around the time of the many theological debates of the Reformation. A friend of mine calls the chapter-and-verse Bible a “debater’s Bible.” But that visual presentation suggests that the Bible is something that it is not. Suppose that all you had of Shakespeare was a collection of “famous quotations.” For example: “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so,” Hamlet, Act 2, scene 2. “What’s in a name? A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, scene 2. “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them,” Twelfth Night, Act 2, scene 5. These are certainly interesting and valuable thoughts to consider and apply to life. But what Shakespeare wrote was drama for the theater. If you haven’t seen his plays acted on stage, you haven’t engaged his writings for what they are. Similarly, if you only reference “Bible verses,” you haven’t engaged the biblical writings for what they are. Another way people engage the Bible is as if it consisted of short articles on various topics, like an encyclopedia. Printed editions of the Bible foster this understanding by separating the text into sections that each have their own headings. People tend to read section by section, and preachers often preach on one section at a time, so this is another answer people have implicitly in their heads to the question of what the Bible is made of. Just by looking at most Bibles published today, they can only conclude that it is made of “sections.” But these sections do not do justice to the literary character of the compositions in the Bible. Translation committees and publishers create and label them not with a view toward literary structure but simply with a view towards subject matter or topic. These titled sections encourage “dipping in” rather than experiencing the biblical compositions as a whole. They also suggest an objective, distanced approach to the topics that are apparently taken up, as in an encyclopedia, rather than that the writers are immersed in the situations they are writing about, sometimes literally in a life-and-death struggle. So engaging the Bible through “sections” is also not engaging its writings for what they are. Yet another way that people engage the Bible is as the subject of an academic discipline. This is what you were asking about specifically in terms of an assessment of Moulton’s analysis. It’s important to realize that when we engage the Bible, there is a “world behind the text,” a “world of the text,” and a “world in front of the text.” The world behind the text is the historical and cultural context in which the Bible was written. Much of academic study of the Bible deals with that. The world in front of the text is the reactions and responses to the text by all the people who are receiving it in various ways. In academic circles, this would be all of the scholars in the field of biblical studies and their various publications. Much of the remaining part of academic study of the Bible has to do with addressing what various other scholars have said about the Bible. Engaging the biblical works as literary compositions is often regarded as outside the scope of biblical studies, as something that falls within the realm of literary studies instead. (And indeed, courses on the Bible are a required part of many college literature majors, since the Bible is such a foundational influence on the literature of many languages and cultures.) The structures of biblical books sometimes are discussed within the field of biblical studies, but my personal feeling is that this is not done in a progressive or cumulative way. In other words, I do not feel that we have come to understand these structures better and better as biblical studies has progressed over the years, so that anything Moulton might have written over a century ago must of course be obsolete by now. Rather—and again, this is a personal feeling—as biblical studies takes up various suggestions about structure in the course of its own conversation, different views come in and out of vogue as the conversation progresses. So for myself, to assess Moulton’s contributions, I would instead ask how the people who, over time, have engaged the biblical books as literary compositions have seen them to be put together on their own terms. This question of literary structure is one (along with the questions of circumstances of composition, literary genre, and thematic development) that Mortimer Adler and Charles van Doren encourage readers to address in their classic work How to Read a Book. It is also a question that various approaches to inductive Bible study encourage readers to pursue first, in light of an overall reading of a book: what are its major and minor divisions? Those are to be determined independently of chapters and verses and of any divisions that publishers have introduced. When we approach the Bible this way, we find, as I show in The Beauty Behind the Mask, pp. 139–143, that the various people who, down through the years, have sought to offer literary-structural presentations of the biblical books have ended up identifying essentially the same outlines, even though these may differ in some smaller details. Richard Moulton is one of these people, and I would say that his overall approach is still one that we can learn much from today. We certainly saw him as someone who helped blaze the trail for The Books of the Bible. Indeed, we knew we were standing on his shoulders as we did our work, and we were and are grateful for his contributions. Let me conclude, therefore, by quoting from his preface to The Modern Reader’s Bible: “The revelation which is the basis of our modern religion has been made in the form of literature: grasp of its literary structure is the true starting-point for spiritual interpretation.” |

Category: Bibles without chapters and verses

Do the blank lines of varying widths in The Books of the Bible signify book sections of varying sizes?

Q, I have a question about The Books of the Bible. I notice that there are blank lines between text, and that sometimes there is one blank line, sometimes two, and sometimes three. Do these correspond with the structure used in Inductive Bible Study? So do three blank lines separate the divisions, two blank lines the sections, and one blank line the segments? I am looking at the Gospel of Matthew. I notice that there is sometimes a blank line separating what I would call paragraphs, and not segments. Thanks.

You are correct. The blank lines identify literary units of varying sizes. In the Gospel of Matthew, three blank lines (and a large capital letter) mark off the largest units. These units are described in the introduction to Matthew: “five thematic sections consisting of story plus teaching,” with a genealogy preceding and a narrative of Jesus’ sufferings, death, and resurrection following. I think you would call these largest units “divisions.”

Two blank lines mark off the next-largest units. Each thematic division begins with a story sequence, followed by a speech sequence (discourse) that elaborates on the theme of those stories. So two blank lines separate story from discourse within thematic units. I think you would call the story and discourse units “sections.”

Three blank lines mark off the smallest units, which are the episodes in the stories or the rhetorical passages in the discourses. For example, there are single blank lines between the episodes of Jesus’ birth, the preaching of John the Baptist, the baptism of Jesus, and the temptation of Jesus. In the Sermon on the Mount, there are single blank lines between Jesus’ discussions of fulfilling the law, the practice of piety (alms, prayer, fasting), and money. I think you would call these units “segments.”

In some cases an episode is brief, only one paragraph long, so in that case a single paragraph also constitutes a “segment.”

These divisions work bottom-up. If a biblical book has literary units on only two levels, then the edition will use only spaces of one and two lines. For example, in 2 John, there are two-line spaces between the opening, main body, and conclusion of the letter. The conventions of letter-writing in the opening and conclusion (sender’s name, addressee, blessing; travel plans, greetings) are separated by one-line spaces.

In The Books of the Bible, there is a brief introduction to each book, and it discusses, among other things, the literary structure that this edition uses blank lines to mark in that book.

I hope this is helpful. Enjoy your reading!

Where can I get an authentic Bible without chapters and verses?

Q. Where can I get an authentic Bible without chapters and verses?

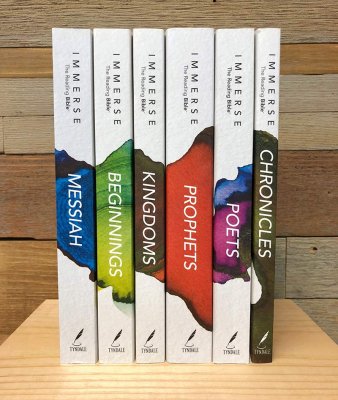

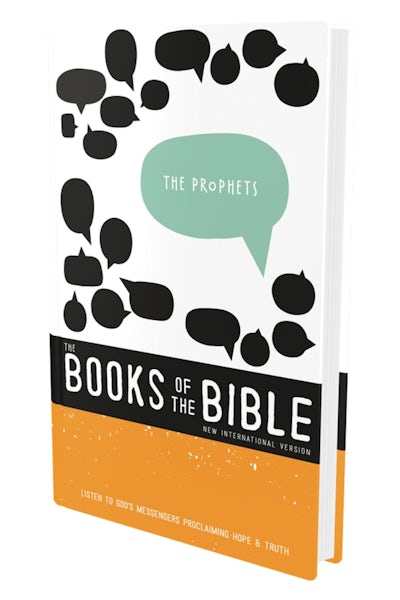

I would recommend Immerse, an edition of the New Living Translation that has no chapter or verse numbers or section headings. It does include book and section introductions. It presents the entire Bible in six volumes. You can order a copy at this link. (Full disclosure: I was a consulting editor for this publication. I receive no royalties or commission or other compensation from sales.)

This is certainly an “authentic” Bible. The New Living Translation is a leading and well-respected English version. Immerse was named Bible of the Year by the 2022 ECPA Christian Book Awards. I hope you enjoy reading it!

(In earlier posts on this blog, I discuss The Books of the Bible, an edition of the New International Version that similarly does not have chapters and verses or section headings. Unfortunately it appears that the publishers have not been keeping this edition in stock. However, it seems that you can still order it, in four volumes, through Christian Book Distributors at this link. I was also a consulting editor for this NIV edition, and similarly I do not receive any compensation from sales. I think you would have a good experience with this Bible as well!)

A Bible reading plan without chapters and verses

Q. I would like to read through the Bible systematically over some period of time, free from chapter and verse interruptions but with approximately similarly sized sections each day, breaking at points that make some sense in context of the text. Are there word counts available for the various sections of Scripture, in order to draw up a reading plan?

Just the kind of reading plan you’re asking about has already been created. As I explain on the “About” page for this blog, I was a consulting editor to the International Bible Society (now Biblica) for The Books of the Bible, an edition of the New International Version (NIV) that presents the biblical books according to their natural literary outlines, without chapters and verses. My work with Biblica also included helping them develop a program of Community Bible Experiences (CBEs), in which groups read through the Bible following a reading plan precisely like the one you’re envisioning.

The CBE resources are now available through Zondervan, the commercial publisher of the NIV. On this site you can get a free digital sample kit that includes reading plans. All you would need to do is buy individual copies of the four volumes in which The Books of the Bible is now being published. But you can order copies through that same site.

I’d encourage you to start with one of the volumes—perhaps the “Covenant History,” Genesis through Kings—and see how it goes. I imagine that you’ll ultimately want to get all four volumes and read through the whole Bible following the natural literary forms of the books rather than the later artificial chapter and verse divisions. Happy reading!

Why is Daniel not among the Prophets in The Books of the Bible?

Q. I have two questions. Our group has read all The Books of the Bible series that are available to date and we are just finishing The Prophets. Why is Daniel not in the Prophets book and instead is slated for the Writings?

Second, Ezekiel is constantly referred to as “Son of Man.” Since this is a reference often used for Jesus, why is it that Ezekiel seems to singled out for same designation?

We have found The Books of the Bible to be an incredible read and one that I feel everyone should experience. Your blog is also a great source for thoughtful answers.

I’ll get to your questions in just a moment. But first, let me thank you very much for your appreciative words! I’m glad your group is having such a great experience engaging the Scriptures in The Books of the Bible format. We’ve heard the same thing from countless others–when the Bible is presented in a way that allows readers to recognize and engage its fascinating variety of literary forms, it indeed becomes “an incredible read.”

You’ve probably noticed that in my posts I often refer to the Understanding the Books of the Bible study guides. These were actually designed to accompany the new format and provide a “next step” for people who “read big” through large portions of Scripture using The Books of the Bible. After you “read big,” the next thing is to “go deep” by returning to one or more of the books in that part of the Bible to study in more detail.

For example, after you’ve “read big” through The Books of the Bible New Testament, you can “go deep” by using the study guides to John or to Paul’s Journey Letters. After reading through the Covenant History (Genesis-Kings), you can look at some of its material in more detail with the help of the Genesis or Joshua-Judges-Ruth study guides. Once you’ve read The Prophets, you can study Isaiah or the Minor Prophets Before the Exile. Ideally a rhythm of reading and studying, of “reading big” and “going deep,” will help a group become deeply steeped in the Scriptures over the years and steadily transformed by the power of God’s word. So if you’re enjoying the discussions here on this blog, I hope you might find the study guides just as helpful in understanding the Bible, but in an even more systematic way, and using the new edition you’re enjoying so much.

But now let me get to your questions. I’ll answer the one about Daniel and The Prophets in this post, and the one about Ezekiel in my next post.

As I describe here, I was a member of the team that created The Books of the Bible. We put the biblical books in a non-traditional order because we realized that the customary order can actually hinder readers’ understanding in many cases. As we explain in the Preface to The Books of the Bible (found in Biblica editions but unfortunately not in Zondervan ones), Paul’s letters “are badly out of historical order, and this makes it difficult to read them with an appreciation for where they fit in the span of his life or for how they express the development of his thought. . . . James has strong affinities with other biblical books in the wisdom tradition. But it has been placed within a group of letters, suggesting that it too should be read as a letter.”

Placing Daniel among the prophets is another way in which the traditional order leads us to have the wrong expectations about a book. Daniel is actually unlike the prophetic books, which consist largely of poetic oracles. Instead it’s made up of six stories of Judeans in exile, similar to the book of Esther, followed by a series of visions that have many characteristics of apocalyptic literature, like the book of Revelation.

In the Hebrew Bible, Daniel is not placed among the Prophets, but among the Writings. It was moved to the prophets in the Septuagint (Greek Old Testament), whose book order our English Bibles largely follow. We felt that the the distinctive kind of literature represented in the book of Daniel could be best recognized if that book were once again placed among the Writings, which we grouped according to literary type in The Books of the Bible. (For a broader discussion of the distorting effects of the traditional book order in the Bible, see pp. 67-75 in my book After Chapters and Verses.)

I hope this explanation is helpful, and thanks again for your encouragement!

What order would you put the books of the Bible in?

You walk in to your adult group at church and the leader gives you a collection of paper strips with the names of the books of the Bible written on them. “What order would you put these in?” the leader asks.

A friend of mine actually did this in the group he leads, and he got some interesting responses.

One person said immediately, “Well, THE order, of course!” For that person, custom and use had already fixed the books of the Bible in THE order, and there could be no deviation.

But others felt freed by the exercise to think about some possible alternatives. One person put books like John and James first and the “hard stuff” last. Why? They said they were thinking about people who were new to the Bible; they wanted to make it more accessible to them. Another person put the books in chronological order so a reader would progress sequentially through time when going through the Bible. And someone else tried to put books together that spoke to the same audience, so readers could see how they addressed similar situations and concerns.

There’s nothing improper about doing an exercise like this. Book order was actually quite fluid for the first three quarters of the Bible’s history. “THE order” that we know today only appeared around 1500 with the advent of printing. Before that, a variety of orders were used, in pursuit of different literary, historical and liturgical goals. So there’s nothing that says various orders can’t still be used today.

The non-traditional order of the biblical books in The Books of the Bible, it should be specified, is not intended to create a new fixed order, another version of “THE order” to replace the conventional one. Rather, that order was chosen because it served the goals of the edition, which were to encourage the reading of whole books with an appreciation for their historical and literary contexts. But other orders could legitimately serve other goals, such as the ones just described.

How about you? What order would you put the books of the Bible in?

Are Jeremiah’s oracles rearranged in The Books of the Bible?

Q. For The Books of the Bible, did you just reorder the biblical books? You didn’t, say, put the oracles within Jeremiah in chronological order? I was just reading Jeremiah in my other Bible and it’s so dang confusing going back and forth between kings and what not. I was wishing the oracles were more orderly.

The creation of The Books of the Bible did not involve any internal rearrangement of biblical books. That was something that our project team agreed early on with the NIV translation committee to leave off the table.

However, the question of internal order within Jeremiah specifically has come up on several occasions over the course of our work. This is because, as the “Invitation to Jeremiah” in The Books of the Bible explains, it appears that a large section of that book has been dislocated.

Jeremiah has four major parts:

1. Mostly poetic oracles, undated, likely not in chronological order.

2. Mostly narratives, dated, but not in chronological order.

3. Mostly narratives, dated, in chronological order.

4. Poetic oracles against the surrounding nations.

The introduction to Part 4, however, is found right after Part 1, suggesting that the oracles against the nations were originally placed before Part 2. This is where they are found in the Septuagint, an early Greek translation of the First Testament.

It would certainly make sense to put these oracles against the nations back in their original location, right after the introduction to them, or at least to read them after that introduction. Accordingly, in the reading plan for the Prophets module of the Community Bible Experiences, Biblica explains how Part 4 of Jeremiah appears to be out of order, so that people can choose to read it after Part 1 if they wish.

As for the lack of chronological order within Parts 1 and 2 themselves, this is due to Hebrew scribes’ preference for “chiasms,” intricate arrangements in which passages that feature certain themes or key words are paired opposite one another.

For example, as the “Invitation to Jeremiah” also explains, at one point in the book a prayer of Jeremiah’s is surrounded by two episodes that feature potters. The very next prayer is surrounded by episodes that feature two men named Pashhur. And these two clusters of episodes are then surrounded by matching episodes relating to the city gates.

Similar chiastic arrangements are found in other prophetic books. As I explain in my Isaiah study guide, for example, many of the arrangements there are “a bit like the kind of trophy case you’d find in the front hallway of a school. The trophies, awards, and plaques in such cases usually aren’t arranged in historical order, from left to right. Instead, the tallest trophy will likely be in the middle, with shorter trophies on each side, and even shorter ones towards the edges of the case—regardless of when they were won. Photos and plaques will be hung on the back wall where there is space and visibility, but not necessarily right behind trophies from the same era. The overall goal is to create a pleasing and appealing visual arrangement. In the same way, the poems, stories, and songs in the book of Isaiah are arranged not historically but artistically, to blend together into an overall message prophetic responses to significant challenges that the people of God faced at different times.”

The same can be said about the arrangements in the non-chronological portions of Jeremiah.

I hope this helps you navigate through that book a bit more easily!

If everyone in a Community Bible Experience is using the NIV, how can they become aware of valid alternatives for translating specific passages?

Q. The Books of the Bible uses the text of the NIV translation. I agree that the NIV is one of the best overall translations. But as some of the conclusions of my studies, I think there are some places where I think they translate the text in a poor way. I accept that translation will always involve interpretation, but I think that in some cases, the translators have misunderstood what the text meant and in some cases it is simply unclear what the authors meant, but the translators made their best guess among a range of possibilities. What do you do when you run into these situations when discussing such texts when reading big chunks in community?

I personally consider the NIV to be the most accurate and readable translation available in English today. But I acknowledge that no translation of the Bible can convey every possibility of meaning that’s present in the original languages.

As you say, sometimes a range of possibilities is present in what an author says, and translators must make a choice among these possibilities. When they do, English readers miss out on the others. Beyond this, translation necessarily requires a tradeoff between wording and syntax in Greek and Hebrew and meaning in English. Different translations will favor one or the other in any given case, with different results conveyed to readers.

Ordinarily, one of the best ways to overcome this difficulty is to make sure that a group of people who are reading and studying the Bible together are using a number of different translations. People will typically speak up when their Bible says something different from someone else’s, and this helps the group appreciate the various ways that words or phrases could legitimately be translated.

But there’s also great value, in an activity like a Community Bible Experience, in having everyone use the same translation. As they each “read big” using The Books of the Bible and then come together to share their observations and reflections, they’ll be drawing on a shared experience of the Scriptures that will allow them to connect with one another quickly and deeply.

So how can the liabilities of a single translation be overcome in a situation like this?

For one thing, typically a whole church will do a Community Bible Experience together, and when they do, the messages in worship will be coordinated with the readings. This provides an ideal opportunity for the preacher to point out and explain any places in that week’s readings that have a range of meanings that one translation alone can’t bring out. (This presumes that preachers will prepare well and study the Scriptures in the original languages, or at least use resources that help disclose their meaning!)

Beyond this, it’s ideal to alternate “read big” experiences of the Bible with “go deep” experiences. After spending several weeks reading through a big chunk of the Scriptures, it’s good for a church or similar group to go back and study one or more biblical books within that chunk for an extended period of time, before reading through another big chunk together. And in that time of more detailed study, it’s natural for people to explore other ways that biblical words and phrases can be understood.

In fact, one of the original ideas behind the Understanding the Books of the Bible study guide series was that they would make a great “next step” for groups that did Community Bible Experiences. The guides are based on the NIV (it’s a privilege to be able to use such a great translation), but in many places they explain the range of meanings implicit in a biblical word or phrase and suggest alternative ways of translating it.

So the “go deep” season of study that ideally follows a “read big” season can, like preaching during a Community Bible Experience itself, provide an opportunity for people to move beyond the necessary limitations of a single translation, without losing the advantages of using that translation for their readings together.

Studying the Bible without chapters and verses

A commenter on this post wrote that The Books of the Bible was “great for just reading,” but that a “regular Bible” was “almost necessary to study.”

In response, I insisted that The Books of the Bible, which takes out the chapter and verse numbers and presents the biblical books in their natural literary forms, actually makes a great “study Bible” as well. That’s how this series of study guides could be created to be used with it (although the guides can be used with any version of the Bible, as this post explains.)

I also promised to share a real-life experience that illustrated what “studying the Bible without chapters and verses” looks like, as related in my book After Chapters and Verses. Here’s the story.

I was recently part of a Bible study group that was going through the book of Daniel. When we took up the third episode in the book, the participants were fascinated to hear how Nebuchadnezzar had made a statue ninety feet high out of gold. Some of them glanced down at the notes in their Bibles and read them out loud to try to help the group understand why he’d done this.

One note suggested that using gold for a huge statue was an ostentatious display of the wealth, power and prosperity of the empire. A note in another Bible observed that a huge gold statue would have been overwhelmingly bright and dazzling. But I asked the members of the study to consider whether anything we’d encountered earlier in the book of Daniel would explain why Nebuchadnezzar had made this statue out of gold.

They thought back to the previous episode, which we’d discussed the previous week. They remembered that the king had had a dream about a statue. Its head was made of gold, but its chest and arms were silver, its torso and thighs were bronze, its legs were iron and its feet were made of iron and clay. Daniel’s interpretation of the dream was that Nebuchadnezzar’s empire, symbolized by the gold head, would be displaced by an inferior empire, which would then be replaced by another, and then another, in the years to come.

In light of this dream and its interpretation, our group recognized that Nebuchadnezzar had created a statue entirely out of gold to offer a direct and very public rejection of the message he’d received from God. He was saying, using the very symbolism of the dream God had sent him, that his own empire would actually last forever and never be displaced. And by insisting that all the officials in his kingdom bow down to this statue, he was requiring them to join him in contradicting God’s revealed vision of the future, and to give their allegiance to him and his empire instead. No wonder Daniel’s friends felt they had to disobey!

Our group wouldn’t have found such satisfying answers to its questions, and we’d have missed an essential dynamic within the book, if we’d simply “read the study notes” and moved on. We got a much greater insight into the passage when we understood how it functioned within the book of Daniel.

But we haven’t been trained to study the Bible this way. We haven’t been taught that we need to read first in order to be able to study afterwards. In fact, we haven’t been encouraged to “read” at all, not in a continuous way. We’ve more often been asked to consider isolated parts of larger works (“chapters” or “verses”) without being shown how they fit within a whole book and how we can appreciate the meaning they have there. We’ve been encouraged to try to understand them instead by looking at other isolated biblical passages in series of cross-references, or by consulting the notes in our Bibles, study guides and commentaries, or asking our pastors, teachers and group leaders.

In other words, our definition of “studying the Bible” has been moving back and forth between the text and explanatory resources. This approach to Bible “study” isn’t effective. The units it engages typically aren’t the structurally and thematically meaningful ones within a book. Even when they are, we don’t appreciate the meaning they receive from their place within the book as a whole. This kind of studying can easily devolve into a running commentary on interesting or puzzling features of an ill-defined stretch of text. It depends on people having an implicit trust in the knowledge and trustworthiness of group leaders and the authors of notes and guides.

We really need to adopt a new definition of what it means to “study the Bible”:  considering the natural parts of a biblical book to recognize how they work within the book as a whole. This means that studying has to be the second step in a process whose first step is reading.

considering the natural parts of a biblical book to recognize how they work within the book as a whole. This means that studying has to be the second step in a process whose first step is reading.

It also means that the best “study Bible” is one like The Books of the Bible that first makes a great “reading Bible.”

Is the Bible what it has become?

In this series I’ve used the following examples to explore generally whether the accumulated marks of an artistic creation’s subsequent history as a cultural artifact become part of its essential substance and meaning. I’ve done this as a means of asking specifically whether chapters and verses and other historical accretions should now be considered an integral part of the Bible:

– The cleaning of the Sistine Chapel ceiling;

– The famous crack in the Liberty Bell; and

– The isolation of the figure from Whistler’s painting Arrangement in Grey and Black as “Whistler’s Mother.”

What can each of these examples help us understand about the Bible?

To take them in reverse order, the detail from Whistler’s painting provides a great example of how “snippets” from an artistic creation can be isolated and given a meaning contrary to the one the artist intended. This effect is particularly pronounced when they’re also given a different name and when other material is added that reinforces the contrary meaning, like the potted flowers in the “Mothers of America” stamp.

This happens all the time with the Bible. Episodes or even sentences are snipped out, isolated, and supplemented, and as a result, even if they still say something edifying, we miss what they really meant in their original context. The “parable of the prodigal son,” for example, is a wonderful story of repentance and reconciliation, but if we don’t see it as only one part of the “parable of the unforgiving older brother,” we miss the overall point that Jesus wanted to make. So there’s a strong case for the approach taken in The Books of the Bible: removing chapters and verses and headings and presenting the books of the Bible as whole literary compositions.

However, the example of the Liberty Bell shows us that sometimes the settings and adaptations introduced by later users can enhance rather than obscure the original creative intentions behind what has become a cultural artifact. This is true of the Bible in the sense that all of its individual works take on a deeper significance (but one that is still consistent with their original meaning) when they are gathered into a collection where they can be read in light of one another and in light of the grand story they all tell together. The Books of the Bible is designed to encourage such a reading by grouping those books that can be read most meaningfully together and by situating each book within the grand story of Scripture.

Finally, the example of the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel ceiling shows that we do become accustomed to engaging artistic creations as they have become known, and that it can be a pleasant surprise (or even an unpleasant shock) to encounter them in something much closer to their original form.

Some people may always prefer what the Bible has become, and see it as a book inherently divided into chapters and verses. But our hope is that through The Books of the Bible, many will be able to encounter the artistic creations (literary compositions) it contains in a form much closer to their original one, and so have a more enjoyable and meaningful encounter with God’s word than they otherwise would have had.